This post is dedicated to Alexander Sodiqov who was arrested about a month ago while conducting research in his home country of Tajikistan. Sodiqov is a University of Toronto student and a Tajik citizen who was conducting interviews for the “Rising Powers and Conflict Management in Central Asia” project when he was arrested. He is accused of spying and treason. This post is much delayed, but sadly, still relevant as Sodiqov has yet to be released.

As an American who wants to research Central Asia, I think a lot about what I should be attentive to since I am not a member of the community that I want to research. One of my biggest concerns when researching communities that I am not a part of is that I may think I understand what people are telling me, without truly understanding. Think back to a time when you told someone your story and then heard them telling someone else their version of your story – if they get it wrong it can make you feel pretty terrible.

Charles Briggs shares an example of this happening in a research context in his book “Learning how to ask.” Briggs is conducting a survey about a facilities center in New Mexico, when he notices that based on his survey, the Navajo residents appear to be much less interested in using the facilities center than other residents. He feels that something is a bit off with these results and he’s right about that. A little more digging reveals that in this Navajo community, it is considered rude to speculate about the behavior of others and so the question “How will you and your family members use the facilities center?” couldn’t really be answered. The problem was with the question, not with the respondents.

This points to the problem of the miscommunication (even in research about communication!) that can happen without insider knowledge. And who has the best insider knowledge? The insiders. This is why it is essential to have partnerships between researchers who are members of a particular community and researchers who are not members of the community.

Researchers who are working in their own communities already know how to ask the questions and they can call out other researchers who are getting non-answers and parading them around as answers. This is important because, if we can get answers and questions that are more true to local understandings then we get better, more accurate research, we do a better job of representing the communities we are studying and we get better solutions to the problems that face these particular communities.

In the case of Central Asia the partnerships between Western researchers and researchers from the region are especially important because Central Asia has been so little understood in the West. This is why researchers like Alexander Sodiqov, who are from the region are so important to the future of research on Central Asia and to the future of relationships between the West and Central Asia.

But one more point – in light of Sodiqov’s detention there has been a lot of talk of “scholars at risk” in Central Asia, but I think it is important to note that not all scholars are equally at risk. Scholars from the region at much more at risk than scholars from the West (due to the relative political power of Western countries and Central Asian countries, and a host of other factors I can’t fully discuss here). I would urge those of us who are invested in Central Asia, but are not from the region to discuss Sodiqov’s case and work for his release with both an awareness of the value he and other scholars from the region bring to our work, and with a special sensitivity to the risks associated with their positions as insiders.

See here for work being done to release Alexander Sodiqov, including a petition that you can sign. See here for the latest article on Sodiqov’s situation.

A few notes: I fully recognize that the lines between outsider/insider are not so clearly drawn and that not all insiders have the same opinions or intuitions. Nevertheless, on a gradient scale there are those with differing experiences and privileges and my hope is that there would be continued dialogue and support between people in different positions on that scale.

Update: Alexander Sodiqov was released after five weeks of being held in prison. He is still being detained in country while there is further investigations into the allegations made against him. For more information, see here.

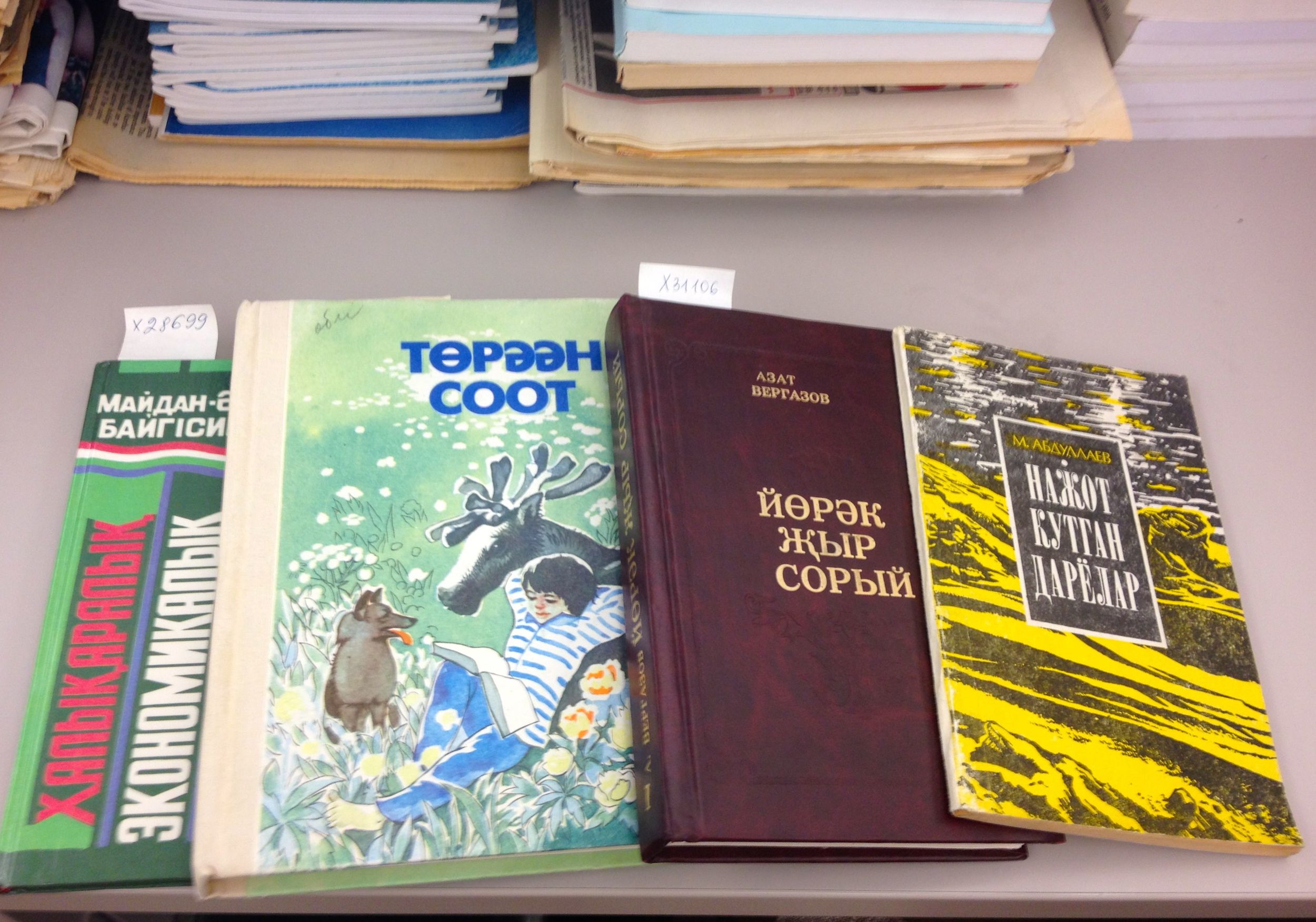

Photo from Creative Commons user, Evgeni Zotov.